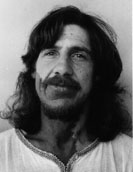

The composer, educationalist and designer of musical instruments, Ron Nagorcka

was born in 1948 and raised on a sheep farm in Tarrington, Western Victoria,

where his father bred superfine merino wool. Tarrington was a small Lutheran

town where life centred around the local school and the church where the young

Nagorcka sang the liturgy and in Lutheran chorales. His mother had been trained

as a soprano and, together with his school teachers, encouraged him to sing.

Later, at the age of 11, he began piano lessons and, before long, J.S. Bach -

whose music was based on the chorales he knew so well - became his favorite

composer.

The composer, educationalist and designer of musical instruments, Ron Nagorcka

was born in 1948 and raised on a sheep farm in Tarrington, Western Victoria,

where his father bred superfine merino wool. Tarrington was a small Lutheran

town where life centred around the local school and the church where the young

Nagorcka sang the liturgy and in Lutheran chorales. His mother had been trained

as a soprano and, together with his school teachers, encouraged him to sing.

Later, at the age of 11, he began piano lessons and, before long, J.S. Bach -

whose music was based on the chorales he knew so well - became his favorite

composer.

Because Nagorcka was a successful student, his teachers encouraged him to continue his education rather than `work on the farm', as most of his peers would have done at age 15. When he was 13 he became a boarder at Concordia College, Adelaide, where he intended to follow his Lutheran education through secondary school and possibly into the Seminary.

Despite the usual confusions of adolesence, perhaps complicated by his rigid religious upbringing, Nagorcka proved a successful student at Concordia where he particularly enjoyed gymnastics, football, tennis and the piano. He also excelled in his academic subjects, and now recalls his favorite teachers, Adele Wiebusch (piano) and Gil Langley (football coach), with affection.

Before his Matriculation (HSC) year, the religious confusion had abated sufficiently for Nagorcka to choose the intellectual challenges of university in preference to the restricted academic scope of the Lutheran seminary. However, since that decision, he has retained a strong interest in spiritual themes, and has studied comparative religion, Aboriginal mythology, Jungian psychology and both Eastern and Christian mysticism. A number of his subsequent compositions are quite religious in nature, particularly the piano piece, Requiem For Ian Bonighton (1976), with its chromatic, yet almost Gregorian theme, and Sanctus , (also 1976) which is discussed below.

In 1965 Nagorcka attended Hamilton High School, became better at tennis and football, made do with a country piano teacher and was dux of the school that year, studying humanities.

However, C.P. Snow's essay on `the two cultures' had been slipped into the syllabus and, after reading it, Nagorcka became determined to explore the `other side' of our culture and returned to Hamilton High School in 1966 to study four science subjects, as well as piano and music theory. Having already matriculated, he found this return somewhat tedious, especially with a more active social life to pursue; and he was also playing A-Grade country football. Still, he managed to pass all his subjects except music theory. Ironically, this opened most doors at Melbourne University except the one to the music department.

Nagorcka decided to pursue a science career because of the "financial opportunities" this seemed to promise. However, he found himself very quickly caught up in all manner of extra-curricular activities at the university during his "first free fling in that hotbed year of 1967": the confusions of sex, politics and religion all resurfaced, demanding most of his time and attention.

At the same time, a number of key friendships were formed which helped re-assert Nagorcka's interest in music. A fellow student, Douglas Lawrence, had an infectious enthusiasm for the pipe organ and Baroque music. He and Nagorcka became firm friends, as did the latter and Sergio di Pieri, the organist at St Patrick's Cathedral, Melbourne, from whom Nagorcka began to take lessons.

In 1967 and 1968 Nagorcka became church organist at Melbourne's St James Anglican Church in East St Kilda and, from 1969 to 1974, at the Church Of All Nations in Carlton, where he concentrated on the interpretation of Bach.

At this time he also began to explore the music of Olivier Messiaen and other 20th Century composers as well as a wide range of popular, blues, folk and rock idioms; and he also played football with the University Blues.

Nagorcka's first year at university was an intense and confusing one, and his 1967 exam results showed it. He managed to fail even geology, despite an extensive rock and fossil collection and an interest in the subject since childhood.

In 1968 he transferred to an arts degree course, studying history, philosophy and music history. Academically he had found his feet again and, for the next four years, studied consistently to gain an Honours Degree in Arts in 1971. He continued to play the pipe organ and learnt harpsichord with Max Cooke (from the Melbourne Conservatorium), who was able to correct fundamental problems in Nagorcka's keyboard technique. From a lecturer at the conservatorium, Meredith Moon, he bought a clavichord which he has played ever since.

In the final year of his degree, he studied a subject called Music D, with Keith Humble and Ian Bonighton. Previously Nagorcka had found university music studies tedious, but here he had working composers as his teachers and a subject specifically designed to examine the music of the present day. During his studies he found the following passage in the book Silence by John Cage:

"Question: But, seriously, if this is what music is, I could write it as well

as you?

Answer: Have I said anything that would lead you to think I thought you were

stupid?"

Nagorcka's dabblings in composition had previously been restricted by a sense of inferiority due to a lack of theoretical training. Cage convinced him that an original composer could legitimately invent his own rules. It might, Nagorcka conjectured, even be an advantage not to have studied years of harmony and counterpoint. Having a clean slate might allow a fresh approach. "Everything we do is music," declared Cage, because the same creative process that produces art and music is involved in all human activities.

To think of it this way was liberating for Nagorcka. It allowed him to overcome his musical inhibitions; and his first real compositions, which date from this time, are rampantly Cageian.

His music was first publicly performed in December 1971 by the group 2 cubed , which consisted mainly of friends with little or no musical training, in a concert titled Experimental Music By Melbourne Composers . Organised by Nagorcka at the Students' Church, Queensberry Street, Carlton, this concert also featured music by Dan Robinson, Ian Bonighton, Rob Maxwell and John McCaughey, which was similarly devised to be performed by `untrained' musicians.

In 1973 Nagorcka's Apathetic Anomaly 1 (1973), a grand happening which employed a cacophony of radios, televisions, record-players and cellos, all scored on cue cards for a multitude of performers, was commissioned by the Melbourne Cello Society and performed at the Royal Park Psychiatric Hospital. The piece fascinated a reporter from the Herald, and was given several pages in that newspaper's `On The Spot' section at the time.

Nagorcka's most enduring early piece was Theme And Variations for pipe-organ , commissioned by Douglas Lawrence for the 1972 Festival Of Organ and Harpsichord , held in various Melbourne venues. It used mainly aleatoric compositional techniques and explored the enormous variety of sound possible on a large pipe-organ. Of the piece Nagorcka wrote in program notes: "there is no message and only one aim - the liberation of sound."

In 1972 Nagorcka studied for his Masters Degree in Music at the University of Melbourne on the topic of Music Education - A Compositional Approach . Formal study in composition at this level was impossible for anyone who did not have the prerequisite theoretical background. Fortunately for Nagorcka his supervisor, Ian Bonighton, was a highly sympathetic teacher and encouraged him in his compositional approach, even though this meant flying in the face of narrow academic strictures - which also proved to be the ultimate detriment of his thesis.

To complicate matters, by late 1972 Nagorcka had become a draft resister, as a stand of conscience against the Vietnam war, and was forced `underground' until the election of the Whitlam government.

Late in 1971 he met the artist Sue Thurgate in Newcastle, while attending the premiere of the film Box by director Bob Mill, for which Nagorcka had written music; and in 1973 Nagorcka and Sue were married in Melbourne.

In 1973 Nagorcka continued his compositional studies with Bonighton and Humble and also taught music at Brinsley Road, an experimental free school based on the Summerhill model and attached to Camberwell High. It confirmed Nagorcka's disaffection with the entire school system and, since 1983, he has taught his own son, Derek (born 1975), at home. The writings of radical educational theorists such as Ivan Illich, Paulo Friere and John Holt had deeply influenced his thinking. In particular, he was attracted by Illich's analysis of "radical monopolies" and the notion of "deschooling society". Nagorcka also became convinced that the institutionalisation of music in any form inevitably removed possibilities of experiment and creative endeavour, that "conservatoria are crematoria," as Harry Partch once said.

Nagorcka felt the need for a complete change and in 1974 the opportunity came when he was awarded a Travelling Fellowship by the Music Board of the Australia Council. He left with his wife for San Diego in the USA, where he became an Associate Fellow at the Center for Music Experiment and Related Research - which was attached to the University of California - until 1975.

Nagorcka was already interested in electronic music, especially because it allowed the composer direct access to and manipulation of source material, but also because it was another area where the old rules seemed superseded and there existed the possibility of an entirely new musical language being created. Few people in Melbourne during the early 70s knew what a synthesizer was, let alone had access to one, and Nagorcka felt privileged to have been able to use the Putney VCS3 set up by Keith Humble in the Percy Grainger Museum at Melbourne University.

At the CME, however, computers were already being used extensively and there was a highly developed analog studio (including a video synthesis facility) managed by graduate student Warren Burt, with whom Nagorcka soon became firm friends.

However, Nagorcka was disappointed by what he saw as an excessive indulgence in the technical at the CME. There, he felt, electronics, rather than allowing new areas of musical exploration, had become a new `field' where `experts' could gain a stranglehold simply by re-presenting outworn musical ideas in new packages.

Not long after arriving in the USA, Nagorcka was also saddened by news of the death, in 1974, of the American composer Harry Partch, whom he had been extremely eager to meet. Partch had always impressed Nagorcka as a composer who, in his philosophy, life and music, had remained consistently true both to himself and his musical inspirations. Nagorcka had previously found Partch's music absorbing when he heard it on record, but the performance of the Partch opera, The Bewitched , presented at San Diego State University by musicians Partch had trained to play, surpassed all his previous experiences and affected him greatly. Here, without electronics or any other technical paraphernalia - other than instruments designed specifically to meet the compositional needs of their builder - was a performance which, like a primitive ritual, reflected the music which generated it. This was Western music, yet its roots ran deep into human pre-history and Nagorcka found it extremely powerful.

Despite the disappointment of not meeting Partch, Nagorcka became good friends with David Dunn, who had been Partch's assistant. Also, because the music department at UCSD had been designed by composers, Nagorcka found many opportunities to discuss music theory with leading musical thinkers of the day. He attended graduate classes with Pauline Oliveros (composition); with Kenneth Gaburo (language theory); Bob Shallenberg (formal logic); Will Ogden (Shoenberg); Bob Erickson (timbre) and with John Silber and Jean-Charles Francois (music education).

He also met the Italian composer Roberto Laneri, then a graduate student at UCSD, whose vocal group Prima Materia improvised drone-like and meditative music using overtone singing and multiphonic chanting techniques. Nagorcka found the sounds Prima Materia produced were reminiscent of the didjeridoo, the subtleties of which he had begun to explore in Australia, in 1973. This was an essentially timbral music, and its interest lay in the investigation of the tiniest intricacies of sound. Nagorcka sang and played didjeridoo with Prima Materia in 1974 and 1975 and his collaboration and friendship with Laneri continues to the present.

In 1975 Nagorcka returned to Melbourne then studied for a Diploma of Education at La Trobe University in 1976, supplementing his student income by helping to build harpsichords in the workshop managed by Mars Macmillan and Alistair Macallister. After improving his carpentry skills, he also explored musical instrument construction and, in recent years, has designed and built everything from sound sculptures to didjeridoos.

In 1976 he was again commissioned to write a piece of music by the Festival of Organ and Harpsichord. The result, Sanctus , for didjeridoo, pipe-organ, voices and electronics, demonstrated many of his Californian influences. The electronic component is limited mainly to the close microphoning of voices and didjeridoo, so a subtle dynamic balance can be maintained with the pipe organ. The piece, which is developed as an improvisation following the didjeridoo part, reverberated through Saint Patrick's Cathedral when it was first performed, with a meditative and almost hypnotic effect upon the audience.

At this time, Nagorcka began to question the status of composition and the position of the composer within society. He found, in Melbourne as in California, that experimental music was largely confined to universities. The gulf between composer and potential audience seemed to be growing rapidly wider, yet Nagorcka dreamed of a community music in which the composer played a more active role.

The opportunity to explore this role was offered when a disused pipe-organ factory in the Melbourne suburb of Clifton Hill was re-opened as a community centre by the Victorian Education Department. Nagorcka, in collaboration with a number of other composers living in Melbourne, collectively instituted the centre as the regular venue for new music performances, and thus the Clifton Hill Community Music Centre came into being in 1976. To perform at CHCMC one simply rang the acting co-ordinator and a suitable date was arranged. Publicity was arranged as cheaply as possible, no one was paid and there was no admission price.

After slow beginnings, CHCMC became one of Melbourne's more intriguing venues, especially when escapees from various academic institutions mingled with punks, poets, performance artists, mum and dad from down the road, serious and not-so-serious artists of all kinds and with the simply curious.

Nagorcka wrote most of his compositions of this time specifically for performance at CHCMC. Most of it employs very simple resources, as instanced by the mammoth three-hour Atom-Bomb trilogy, scored almost exclusively for voices, toy instruments and cassette tape recorders.

Very little of Atom Bomb is pre-recorded. The performers originate sounds then, using tape recorders, manipulate them by following carefully detailed instructions; and the whole event is precisely scored as a piece of music theatre. The concluding part of each section of the trilogy is a playback, from each of the four corners of the room, of the tapes that have been generated during the performance.

At this time Nagorcka and Warren Burt formed a duo called Plastic Platypus which crowned its career with a tour of Europe in 1979. Altogether they gave 19 concerts, at London's Institute of Contemporary Art, the Palais de Beaux arts in Brussels and at various venues in Cologne, Oslo, Bath, Cardiff and other cities. Performances included Atom-Bomb , variations on Love Me Tender , by Elvis Presley, and Somnambulism , a piece in which one short burst of didjeridoo sound is developed into a huge and dense texture, an elaboration made possible by changing speeds on cassette recorders and swinging light loudspeakers through the air like bullroarers. Plastic Platypus presented a form of music theatre, in which the theatrical component consisted of novel methods of producing and arranging sounds. As in the Institute For Dronal Anarchy - a group Nagorcka formed with Ernie Althoff and Graeme Davis in 1980 - there was strong emphasis on alternative forms of musical presentation in the post-Cageian experimental tradition.

A notable piece from this period was Seven Rare Dreamings (1981) written in collaboration with Ernie Althoff. In this piece all Nagorcka's preoccupations of the time are reflected. It begins with an Aboriginal legend about the origins of the didjeridoo; an abstract drama develops in which a computer takes an active part on stage, producing everything from synthesized video patterns, twelve-tone music, randomly generated poetry and a long drone in which overtones develop to match those of the didjeridoo and Althoff's prepared saxophone. The roles of expert, academic and devil's advocate are all played by Althoff using an extensive array of homemade masks and props and the entire piece is set in semi-darkness against a slide backdrop of terracotta dragons from the rooftops of Melbourne.

Seven Rare Dreamings highlights Nagorcka's interest in the didjeridoo, which he began to play in 1973. Self-taught and originally interested in the instrument purely for its musical qualities, playing it led him to undertake a thorough examination of Aboriginal culture and mythology.

In 1979 while visiting Roberto Laneri in Italy, Nagorcka recalls playing the didjeridoo for a small group of people in Rome when a girl in the audience fell into a trance. Later, through a translator, Nagorcka asked her about it and she said, "I don't know what it means, but I pictured a rainbow and a snake".

Legends about the origins of the didjeridoo describe the instrument as the `voice' of the Rainbow Serpent. Nagorcka says the incident made him more aware of "the reality of the Dreaming" which Aboriginal friends in Melbourne had sometimes hinted at. Australia, Nagorcka believes, seen through the mythology of the Dreaming, was once a place full of magic and what one writer described as a "vast culture of the mind". Through the mythology of European science and the market economy, it has become a frontier to exploit - resulting in a brash young culture which still gives little thought to the genius of the many varied cultures it has destroyed.

From 1977 to 1981 Nagorcka worked as a lecturer in composition and music education at Melbourne State College, and from 1979 collaborated with composer and musician Rob Williams in the presentation of creative music workshops. Together they developed a program designed to stimulate activity in and discussion of all areas of contemporary music, all at the initiation of the students.

In 1982 Nagorcka was appointed music consultant to a region of Melbourne Catholic primary schools. While he found that primary school children generally display a great deal more initiative than tertiary music students, the problems of dealing with yet another set of institutional administrators, as well as severely over-worked teachers, convinced him that short-term poverty was a more attractive option. (His marriage had ended a little earlier.)

After returning from Paris in 1983, where he presented his music at the Festival de Automne, he moved with his son from Melbourne to the country town of Woodend in the Macedon Ranges, where the tasks of building his own house and studio and pursuing a long interest in alternative living in the bush have kept him occupied. At Woodend he also taught piano to private students and organised a carpentry workshop and a basic electronics studio.

From 1983 to 1986 Nagorcka wrote two substantial compositions: one of these, The Spirit Of The Place, Part 1 - Dawn In The Black Forest , seems uncharacteristically neo-romantic, but it demonstrates his major interests of the past 10 years. Scored for violin and clavichord, it incorporates a tape of the composer playing the didjeridoo at dawn in the Black Forest near his home, all set against a background of raucous cockatoos. Here we have the use of basic electronic technology, the exploration of new and different sounds on traditional instruments, a large element of improvisation for the performers (who follow a fairly simple score) plus Nagorcka's continued fascination with the didjeridoo, Aboriginal culture and the Australian landscape.

In 1986 Nagorcka invited Roberto Laneri to visit Australia and the two composers performed together at various venues, such as Trinity College Chapel at Melbourne University, and during the Perth Festival of Improvised Music. The pieces they presented included Laneri's Two Views Of The Amazon and Gya Gya Gya and Nagorcka's Sanctus and Dawn In The Black Forest .

Nagorcka's recent projects include further pieces in The Spirit Of The Place series. These were written for a tour of Europe - again with Roberto Laneri and the Prima Materia ensemble - and for a series of concerts in Rome, Munich and Vienna, plus workshops in Vienna and four days of studio recordings with Berlin Radio, all in late 1987.

RECORDINGS

"Theme & Variations for Pipe Organ", Reverberations I , Move Records MS 3008, 1973.

"Sanctus", Reverberations II , Move Records MS 3025, 1979.

"Atom Bomb (excerpt)", NMATAPES 2 , NMA Publications, 1983.