|

|

|

|

|

|

Altering consciousness through music

a speculative methodology

Rainer Linz

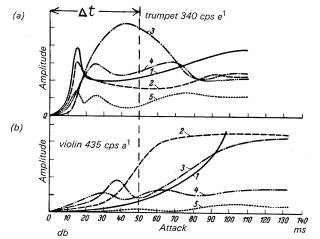

The question of composition with physiologial parameters necessarily involves some degree of speculation, and of course there is a danger in that. With this in mind I want to begin[1] by saying that the Twentieth Century has a demonstrably different relationship to music than previous centuries. I am referring to the mass media, to the availability of sound recordings [i.e. CDs] and the many advances in electronic and computer music. Today, when virtually every aspect of music is under the microscope, how can we talk about a "new music"?From the 1950s we have inherited a number of promises regarding the future of music, namely that music would be made using sounds of

- any frequency

- any loudness, or dynamic

- any timbre

- any character of onset or attack, and

- any rhythmic duration or in combination of rhythms

Many of the possibilities opened up since the 50s depend on the availability of new technologies. But what has become of the promises? What has happened to the music of the future itself? For one thing we can detect a new kind of functionalism in the way it is practiced, in particular (as in music therapy) an emphasis on the influence of music on different forms of behaviour.

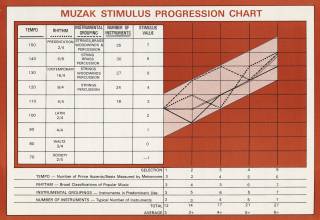

A stimulus/response form of composition has found its most comprehensive expression in Muzak, created by the Muzak Corporation since the 1930s and 40s. Because Muzak has no dynamic variation (through the use of compressors in the recording process) it relies for its 'stimulus value' on combinations of tempo, rhythm, instrumentation and orchestra size. The independent variables are ordered into a scale of values and combined together in the arrangement of popular tunes, to arrive at an overall stimulus rating for a piece. Individual pieces are arranged in succession to produce a gradual rising and lowering of stimulus value over a longer period.

Expanded musical resources are applied in this way to structures which can appeal in a physiological rather than an emotional way (though there is a relationship between the two). As I have said this involves considering music as a stimulus - deliberately bypassing or making ambiguous the intellectual processes which may be brought to bear by a listener.

-

It is possible to assert that humans have constantly-altering states of

consciousness, in that any sensory input will subtlely affect the way that we subsequently

perceive things. Here I want to focus initially on those alterations to

consciousness that can be said to be gross i.e.

trance, hallucination, meditative states and so on. These 'signpost' states are usually

triggered by outside stimuli whose effect on our physiology can be measured

- using EEG, GSR, ECG and other parameters.

-

In discussing music and altered states of consciousness it is often overlooked

that music plays only a part in the total fabric of the stimulus. Trance

ceremonies for example can involve

deprivation of food or sleep, manic movement, singing, ritual, spiritual

beliefs, expectation - in short a whole gamut of both physical and

psychological factors in a scenario affecting all of the senses.

-

In music, the sensory input generally comes through the ears only.

Even so, music has an ability to alter our physiology:

-

Wilson and Aiken

[2]

found that playing loud rock music to subjects produced decreased skin

resistance (GSR), increased rate of breathing and cardiac decelleration - i.e.

a model arousal response.

- A tape loop [3] of a lullaby played to a resting subject was found to cause his breathing rate synchronise with the phrasing of the music.

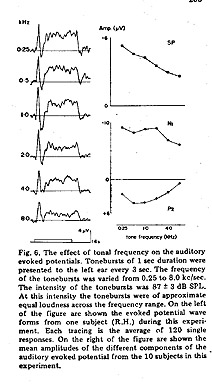

- Neeher [4] observed "auditory driving" of brain activity using a 120dB snare drum stimulus at 4,6,8 and 12 Hz. ("Photic driving" - responses to repeated flashes of high-intensity light - could be detected in the brain since 1934. In 1946 it was found that photic stimulation produced model epileptic responses in brain pattern - and in some cases led to epileptic seizures. This has not been found with auditory driving, or "auditory evoked potentials".)

- The influence of music on human physiology has been the subject of modern scientific enquiry since the Nineteeth Century [5] .

The various physiological parameters, which can be measured and given a value, in combination provide a physiological map of different mental states.

-

Wilson and Aiken

[2]

found that playing loud rock music to subjects produced decreased skin

resistance (GSR), increased rate of breathing and cardiac decelleration - i.e.

a model arousal response.

-

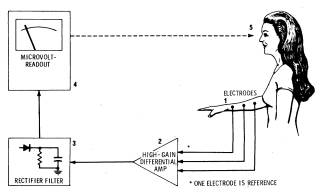

One line of investigation into altered states of consciousness and music which

approaches a method or technique involves the use of biofeedback. This includes

monitoring physiological parameters and attempting to consciously alter performers' mental states. It

has also been popular as an aid to reducing tension and stress. Physiological

parameters that can be monitored include the Galvanic Skin Response (GSR) or skin conductance,

Electrocardiogram

(ECG) or heart rate, Electroencephalogram (EEG) or brainwave, Electromyogram

(EMG) or Muscle activity, Eye Movement Potential, Blood Pressure and

Respiration (rate and depth). These readings give information about the state

of consciousness and have been used primarily in meditative experiments with music.

The strength of the feedback loop is important. A weak loop presents information to the visual or aural senses, and any possible alteration of physiological state is voluntary. Here a number of factors can mediate the effectiveness of the loop including environment, level of relaxation/exhaustion, degrees of willingness, the role of physical movement and so on. Strong loops use monitored information to directly alter other aspects of the physiological state, eg an electrocardiogram is used to trigger light flashes which in turn control the eye movement or produce brainwave driving etc. Powerful and complex relationships can be forged using strong loops.

-

Attempts to alter the state of consciousness through music will be more

successful if other senses are involved. There are two opposite points of

departure

[6]

:

- Sensory deprivation (static) - where hallucination can occur after a short while. This usually involves 'masking' the senses for example by use of eyeshades, and allowing as little environmental intrusion as possible.

- Sensory bombardment (dynamic randomised fluctuation) - where hallucination can occur after c.30 minutes. This may involve extremes of temperature, loud music, bright lights, strong smells (or tastes) and exaggerated physical movement.

In either case there is no tangible fixed point of reference for the senses to function normally. It is in these two areas that most experiments have been carried out because individual parameters can be considered in isolation and in relation to others, using a scientific approach.

All techniques for achieving powerful generalised psychic states involve the disorientation of the subject's usual resting relationship to the outside world.

-

At present attempts to reproduce music centre on the moving coil

loudspeaker and derivative technology. Although there is a large variety of

input transducers

made to convert changing energy patterns into electrical energy - photocells,

thermistors, pressure transducers microphones and pickups, scalp electrodes -

the range of

output transducers

remains limited.

One notable exception is the "colour organ", a form of sequence-lighting dependent either on frequency or amplitude of input music, using ordinary incandescent light bulbs. A triggered strobe light is another example.

Another transducer commercially available is the Soundulator (used for installing sound into swimming pools) which is based on the moving coil loudspeaker. These transducers have been used to vibrate virtually any conceivable object, but I am not aware of any experiments where these have been used directly on the human body.

-

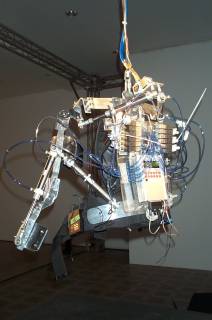

It is necessary then, to develop other transducers which can have a direct physical

effect on the human body, vibrating its parts or causing it to move in

predetermined ways.

- Helmets which shake the head.

- Listening chairs that bounce up and down.

- Floors and walls that vibrate at every frequency.

- Music-modulated electric currents passed through muscle tissue.

- Lights whose intensity and colour, and on/off rates, are controlled by musical input.

-

Techniques of operant conditioning will become useful in a study of the

altered state of consciousness in

relation to music. (This has its own theatrical aspect, but that is another

matter). Experiments carried out by operant conditioners have already supplied such

data as thresholds of pain and possible degrees of driving etc, which will

become useful as design parameters for new transducers.

Nevertheless a number of problems still need to be resolved before these attempts can be brought before an audience. Not the least of these is audience expectation and reaction. Driving techniques will mean that active participation from an audience is no longer necessary.

Footnotes

- From an unpublished talk given at a Wollongong music camp during 1980. return

- Wilson, CV and L.S. Aiken. The effect of intensity levels upon physiological and subjective responses to rock music . Journal of Music Therapy vol XIV(2) 1977 pp60-76. return

- Kneutgen, J. Eine Musikform und ihre biologische Wirkung Zeitschrift für experimentelle und angewandte Psychologie Vol 17(2) 1970 pp 245-265 return

- Neeher, A. Auditory driving observed with scalp electrodes in normal subjects. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology Vol 13 1961 pp449-51. return

- For a review of earlier work see Diserens, CM. The Influence of Music on Behavior Princeton University Press 1926. return

- see Manfred Eaton, Bio Music Something Else Press 1974. return

back to index page.